|

Up

Up

Rheims

Rheims

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

hen

the suit was filed, Curtiss was no longer in America. He was in France

with yet another new airplane, similar to the Golden Flyer but with

a shorter wingspan to cut down on the drag and a more powerful engine to

increase the speed. He called it the Rheims Racer. hen

the suit was filed, Curtiss was no longer in America. He was in France

with yet another new airplane, similar to the Golden Flyer but with

a shorter wingspan to cut down on the drag and a more powerful engine to

increase the speed. He called it the Rheims Racer.

The French had organized the first international aviation meet,

officially known as La Grande Semain d'Aviation de Champagne, in

the ancient cathedral city of Rheims. Twenty-two airmen from all over the

world attended, bringing with them 38 airplanes, 23 of which actually made

it into the air — an astounding display of airmanship. The planes

represented 10 different manufacturers. Most of the aircraft were French

— Voisons, Bleriots, Antoinettes, and Farmans. There were also 6

French-built Wright aircraft, although the Wright brothers themselves did

not attend. Curtiss and his Rheims Racer were the only American and

the only American-built airplane present.

It was a grand affair. The air meet was backed by the city of Rheims

and the neighboring vinters, who cleared Bethany Plain near the city and

built an "aeropolis." The ten-square kilometer flying field

boasted hangers, grandstands, barber shops, florists, and a 600-seat

terrace restaurant where spectators could sip champagne and listen the

fiddlers as they watched the air races. The aviators arrived like knights

and nobles with elaborate entourages, including ground crews, equipment,

and spare airplanes. Gabriel Voison brought an entire field kitchen and

the cooks to man it.

By contrast, Glenn Curtiss had two mechanics, a single airplane, and a

spare propeller. But the austerity and simplicity of his operation

endeared him to the French, perhaps because it remained them of the

simplicity of Wilbur Wright just a year ago. He quickly became one of the

favorites with the aviators, spectators, and newspapers.

The last was something of consternation to Curtiss. Before he left, he

had labored night and day to perfect a new 50-horsepower motor. He thought

of it as his edge, by which he might win the speed competition and capture

the Gordon Bennett Trophy, the most coveted and important award at Rheims.

But the newspaper soon spread the word of his marvelous engine, and Louis

Bleriot quickly had one of his airplanes fitted with an 80 hp motor.

"When I learned of this," said Curtiss, "I believed my

chances were very slim indeed, if in fact they had not entirely

disappeared."

One of his mechanics, however, bucked him up. "Glenn," said

Tod Shriver, recalling their old motorcycling days, "I've seen you

win many a race on the turns."

The air meet opened to bad weather on the morning of August 22. But by

late afternoon, the skies had cleared, the winds were still, and seven

airplanes took the skies together. It was an incredible spectacle that

awed everyone present, aviators and spectators alike. Curtiss, however,

held back. He avoided exposition flights and chose not to participate in

the endurance competition. He had only one plane and one motor, and he

could not risk them before the speed trials.

He did, however, make a number of short practice flights to get

familiar with his new airplane and make sure it was working properly. On

the second day of the meet, he took to the air and set an unofficial speed

record of 43 mph. His triumph was short lived, however. The next day

Bleriot topped him with 46 mph.

Curtiss and his mechanics began to tinker to see if they could coax a

bit more speed from their airplane. They removed the bulky gas tank and

replaced it with a slimmer one to reduce drag. They contemplated buying new

propellers to increase thrust and fussed over the engine, trying to coax

more power from it. Bleriot, too, was tinkering with his airplane. When a

minor accident necessitated repairs, he cut down the wings, making them

slimmer. This reduced his lift slightly, but it also reduced drag.

On the day of the Gordon Bennett cup race, Curtiss made his speed run

as early as he could. "I climb as high as I thought I might without

protest, before crossing the starting line — probably 500 feet — so

that I might take advantage of a gradual descent throughout the race, and

thus gain additional speed." Over the starting line Curtiss nosed

over slightly and began to pick up speed. "I cut the corner as close

as I dared and banked the machine high on the turn," he recalled. On

the backstretch, flying as fast as he could, he smashed into an invisible

wall of turbulence. "The shocks were so violent that I was lifted

completely out of my seat," said Curtiss. At this point, the prudent

thing to do was to power back to keep the machine from shaking to pieces.

But Curtiss powered through the thermals and reached smooth air again.

When he landed, a mob of cheering Americans rushed him. He had set a new

world's record — 46.5 mph.

Other aviators had yet to fly, however. As Curtiss watched "like a

prisoner awaiting the decision of the jury," one by one they flew and

fell short of his mark. There was no serious competition until it was

Bleriot's turn. On the first leg of the course, Bleriot's trimmed wings

seemed to be giving him the edge — his first circuit was four seconds

faster than Curtiss. But the winds had become gusty, and Bleriot had to

fight to maintain a true course. He landed to thundering applause from the

French and walked over to the judges booth. Curtiss remained a respectful

distance. The crowd was dead quiet and remained that way until suddenly

the silence was pieced by a shriek of joy. The shout came from Courtland

Bishop, president of the Aero Club of America, who was in the judges

stand. He came running over to Curtiss. "You win! You win!" he

shouted. Curtiss had beaten Bleriot by just six seconds.

The Gordon Bennett Trophy was his. Newspapers would dub Curtiss

"Champion Aviator of the World," and he would return to a hero's

welcome in New York. More importantly his fame — and the reputation of

his airplanes — now rivaled the Wright brothers.

|

The Rheims Racer in its final

form with shortened wings.

The cockpit of the Rheims Racer.

Glen Curtiss at the controls of the Rheims Racer.

A pylon race at Rheims.

Although the Wrights did not attend the Rheims Air Meet,

their airplanes competed. This Wright Model A was flown by LeFebre, the

chief test pilot for the Wright Company in France.

Curtiss over the grandstands in Rheims.

A worried Bleriot watches Curtiss' performance.

Close-up of Curtiss passing by the grandstands.

Curtiss' victory parade at Rheims.

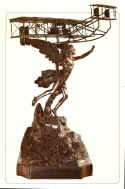

The Gordon Bennett Trophy.

Curtiss' triumph was front page news in newspapers and

magazines across the United States.

The Rheims Racer went on display in Wannamaker's

department store in New York City after returning to America.

|