|

Up

Up

1906 Aero Club

1906 Aero Club

Exhibition

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

[Ed. – In late 1905, several members of America's technological

elite organized the Aero Club of America. It had already been

operating informally for over a decade, but in November 1905 they

adopted a charter patterned after the

Aéro Club de France. One of the purposes

of the formalized ACA was to share and disseminate information about the emerging

field of aviation and aeronautics. It's very first undertaking was

to stage a trade show at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City,

bringing together flight-minded folks from all over America and

Europe. From January 13 through January 20, the Aero Club of

America Exhibition of Aeronautical Apparatus showed the state of the

flying art in 1906.

It was a turning point in aviation and no one felt its effects

more than the Wright brothers – even though they just barely

participated. At the invitation of

Dr. Albert Zahm of Catholic University, they paid the $20

membership fee to join the club. (Zahm was an acquaintance of theirs

with whom the brothers had corresponded about their wind tunnel work

and powered flights.) They then sent the

crankshaft and the flywheel from their damaged 1903 Wright Flyer

engine, along with a few photographs – but they did not go

themselves. The same week that the exhibition opened, Scientific

American magazine published a snarky editorial entitled "The

Wright Airplane and its Fabled Performance" intimating that the

Wrights had grossly exaggerated their success in a report they had

sent to

Ferdinand Ferber, a member of the

Aéro Club de France. This was in contrast to

the photos the Wrights had sent to the exhibit, which showed their

success was real.

It also contrasted with letters that Zahm had exchanged with the

Wrights and a report that

Charles Manly had given to the Aero Club of New York on 14

November 1905, describing the test flights of the Wright brothers in

1904 and 1905. (Manly may have surreptitiously witnessed some of

those flights.) Manly, Zahm, and other Aero Club members in the know

apparently talked to aeronautical

enthusiast William J. Hammer. Hammer was an accomplished scientist

who had helped Edison develop the electric light and first proposed

radium as a treatment for cancer. He was also a founding member of

the Aero Club of America and had an extensive photo collection of

aeronautical experiments which he displayed at the exhibition.

The conflict between the

Scientific American article and other reports that he was hearing

peaked Hammer's curiosity.

After the show, Hammer traveled to Dayton, Ohio and talked to the

brothers. He came away certain that Orville and Wilbur had not

exaggerated their accomplishments. He went back to New York City and

convinced other members of the club to endorse the Wrights.

Dr. Alfred Zahm, because he was already their acquaintance, was

asked to contact them. In a letter to the

Wrights, Zahm suggested they prepare a statement describing their

experiments and that the Aero Club would adopt it as a resolution.

"This would be the first formal identification that your countrymen

appreciate your work and are proud of it. It may also prove of

historical value in showing that the specialists of your day regard

you as the inventors of the first successful flying machine."

The Wrights were agreeable; the Scientific American

article had stung. Another in a German magazine had plainly called

them "bluffers." They had been secretive while developing their

airplane, staying out of the news until their patent was secure. But

now it was time to be more forthcoming. They didn't yet have their

patent – it would not be granted until May 22 of that year – but no

doubt their lawyer had told them their application had passed the

Patent Office's litmus test. So they wrote

a straightforward account

of their flights at Huffman Prairie which the Aero Club adopted and

published along with its own resolution in March. Within a few

weeks, Scientific American conducted their own investigation.

On April 7, the magazine told its readers that "There is no doubt

whatever that these able experimenters deserve the highest credit

for having perfected the first flying machine of the

heavier-than-air type which has ever flown successfully and at the

same time carried a man."

The following is Scientific American's description of the

Aero Club of America Exhibition of Aviation Apparatus. It's a

snapshot of American aeronautics just as the Wright brothers began to

have an effect.]

From Scientific American,

Volume XCIV, No. 4, January 27, 1906, pps. 93-94

A most interesting exhibit, in connection with

the Sixth Annual Automobile Show held recently in the 69th Regiment

Armory, was that made by the newly-formed Aero Club of America. This

exhibit was the most complete of its kind ever held in any part of

the world, for all types of flying machines, balloons, and airships

were represented. In the same room with Santos-Dumont's No. 9

airship was to be seen one of the original gliding machines of Herr

Otto Lilienthal, as well as the gasoline and steam-propelled

aerodromes of Prof. Langley and the motor-driven aeroplane models of

Herring and Hargrave. Other apparatus shown consisted of Prof.

Bell's tetrahedral kite, Ludlow's combined box kite and aeroplane,

Myer's electrical torpedo, and Kimball's heliocoptere. The original

Hargrave box kite was also shown, as well as numerous models

designed by Herring and Chanute. Besides these very complete

exhibits of apparatus, the walls of the room were covered with a

large collection of photographs showing the machines of other

inventors, such as Whitehead, Berliner, and Santos-Dumont; and other

photographs showing airships and balloons in flight, together with

bird's-eye views taken from the same. In another room cinematograph

exhibitions were given twice every day. The views shown consisted of

motion pictures of the Vanderbilt automobile race, the Mount

Washington hill climb, balloon ascensions, and experiments in

raising aeroplanes when towing them by means of a motor boat. In

showcases placed in the exhibition hall were seen primitive models

of flying machines from the Patent Office at Washington, light

motors and other appliances for aeronautical work, together with a

collection of books bearing on the subject. Among the exhibits of

apparatus of historic interest were the large wood propellers which

Mr. Herring used on the first motor-driven, man-carrying aeroplane

to make a flight from the ground. This machine, according to Mr.

Herring, was propelled by a small compressed-air motor. On October

22, 1898, he informs us that it flew with its operator a distance of

72 feet in S seconds against a 25-mile-an-hour wind. Another exhibit

of great interest at the present time, in view of the claims of

remarkable flights made by the Wright brothers last summer, was the

four-throw crankshaft and flywheel of the motor said to have been

used on their machine when, on December 17, 1903, they made their

first flight with a motor-driven aeroplane at Kitty Hawk, N. C.

These experimenters claim to be using the same cylinders with their

latest machine, the motor of which they have fitted with a lighter

crankshaft. The crankshaft shown weighed in the neighborhood of 30

pounds.

Among the model self-propelled aeroplanes

shown, those of Prof. Langley should undoubtedly have first mention.

The steam-driven machine flew about half a mile over the Potomac

River at Quantico, Va., a little less than ten years ago, or on May

6, 1896. This was the first flight of a motor-driven aeroplane. The

gasoline-propelled model (which has a five-cylinder air-cooled

motor, the cylinders being arranged in a circle) made numerous

shorter flights in August, 1903. Prof. Langley's models are

constructed on the following plane principle. The original inventor

of this device, which was first brought out about 1878, was Mr.

Brown, and samples of Brown's "bi-planes," as they are termed, are

shown on page 93. A lift of only about 20 pounds to the horse-power

is possible with this system, as against a lift of from 100 to 150

pounds per horsepower with the superposed plane type. In actual

practice Langley obtained about 18 pounds lift. Langley's complete

steam machine weighed 30 pounds, while the motive plant developed

11.4 BHP. The gasoline model was one-quarter the size and

one-sixteenth the weight of Langley's man-carrying machine. It

weighed 58 pounds, of which 10 pounds was in the 10 horsepower

engine. As to the actual flights of these machines, there can be no

question, for the one on the date mentioned was witnessed by Prof.

Bell, and photographs were taken of the machine in flight.

Another interesting model is that exhibited by

Mr. Herring, and which he claims has made numerous successful

flights. When tethered to a high pole with a long cord, this machine

is said to have flown 15 miles in a circle in December, 1902, and to

have stopped only when the gasoline supply gave out. A

single-cylinder, air-cooled gasoline motor having

mechanically-operated inlet and exhaust valves and a make-and-break

igniter, all worked from a single cam, and carrying a small

propeller on its crankshaft, was shown on this machine. The weight

of the motor was said to be only 2 pounds, and its maximum

horse-power 0.51 at 3,400 RPM. In flight, however, the engine only

made about 850 RPM. and developed but 0.07 horsepower. The aeroplanes of this model (which is shown in the lower left-hand

picture on the preceding page) were 5-1/4 feet long by 14 inches

wide, and the 19-inch propeller which was fitted drew them through

the air at a speed of about 30 miles an hour. This machine is of the

usual rectangular, curved, superposed plane type invented by Chanute

and Herring about the year 1896. Its successful operation is said to

be due to an equilibrium-maintaining device which its inventor

prefers to keep secret. No photographs of this or of larger

man-carrying machines in flight were shown, nor has any trustworthy

account of their reported achievements ever been published. A single

blurred photograph of a large birdlike machine propelled by

compressed air, and which was constructed by Whitehead in 1901, was

the only other photograph besides that of Langley's machines of a

motor-driven aeroplane in successful flight. In order at least

partially to substantiate their claims, it would seem as if

aeroplane inventors would show photographs of their machines in

flight. This has been done by Mr. Maxim and Prof. Langley; and on

account of his desire to secure photographs of his tetrahedral kites

in mid-air. Prof. Bell uses red silk in their construction instead

of nainsook, which he prefers, but which, owing to its light color,

is difficult to photograph.

In contrast to the great secrecy of the later

aeroplane experimenters, should be noted the free manner in which

that first great experimenter in gliding flight, Otto Lillenthal,

gave the results of his experiments to the world. One of the early

gliding machines used by him in 1893 was exhibited, and a photograph

of this machine is to be seen on page 93. Had it not been for his

untimely death in 1896, from the breakage of his machine while in

flight, there is scarcely any doubt that he would have solved the

problem of the motor-driven aeroplane some years ago; for he was not

only a thorough mathematician and physicist, a clever constructor

and mechanical engineer, but he was also possessed of that daring

and physical dexterity which is a valuable aid to one attempting to

solve such a problem.

One of the most interesting exhibits was Prof.

Bell's tetrahedral kite shown on the preceding page, and a 408-cell

model of the huge 1,300-cell man-carrying kite "Frost King," which

was fully described in Supplement No. 1432, and which carried over

280 pounds. Despite the apparent frail structure of these

tetrahedral cells, their great strength when assembled was

demonstrated by the placing of a 190-pound man upon a mass of 100 or

more without damage. The kite we illustrate, by means of its tipping

tail worked by a pendulum in the bow, will descend in long graceful

curves when released in mid-air, and several times it has described

complete circles before alighting, in much the same manner as does a

soaring bird.

Among other interesting exhibits were examples

of balloon wicker baskets equipped with appliances for sketching and

photographing the country, and for making weather observations. The

frames of two dirigible balloons, the "Santos-Dumont No. 9" and "The

California Arrow," were exhibited. Both were equipped with

air-cooled gasoline motors of the lightest construction.

A complete set of apparatus used by the weather

bureau formed still another extremely interesting exhibit.

The greatest credit should be given to the

Committee of the Aero Club, and especially to its able secretary,

Mr. Augustus Post, for the exhibit made at the Armory. Not only will

this exhibit tend to stimulate interest in the art of flying, but,

followed by the active interest of the Club in matters pertaining to

the art, it should greatly promote the development and perfection of

the practical flying machine.

In Their Own Words

- Pulling Back the Curtain

– At the request of the Aero Club of America, the Wrights publish the

results of their 1904 and 1905 experiments at Huffman Prairie for the

first time.

|

One room of the 1906 Aero Club Exhibition in the 69th Regiment

Armory in New York City. An original Lilienthal glider and

Chanute-Herring glider are suspended overhead. William J. Hammer's

photo collection is displayed on the wall to the left. The

crankshaft and flywheel from the 1903 Wright Flyer engine is on a

display table at the right. Interesting note: These engine parts

were never returned to the Wright brothers. The engine on the original Flyer in the Smithsonian

Air & Space Museum was

built in 1916, pieced together from the remaining original parts and

many new ones -- including a new crankshaft and flywheel.

Alexander Graham Bell (lower center) displayed his tetrahedral kites

in an adjacent room in the Armory. (Bell would eventually see his

associate John McCurdy fly a tetrahedral wing aircraft is 1912.)

Overhead is the gondola and engine from Alberto Santos-Dumont's

Airship No. 9.

The cover of the January 27, 1906 edition of Scientific American

showed a huge crane designed to construct a warship.

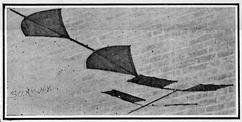

Side and End Views of Prof. Bell's Tetrahedral Kite, Which, When

It is Released in Mid-Air, Descends in a Series of Curves, and

Sometimes Describes a Complete Circle Like a Soaring Bird.

This photograph shows the rear of the kite, which is made up of

tetrahedral cell constructed of spruce sticks 4mm (0.157 inch) and

25 cm (9.843 inches) long, bound together with fine twine and

covered with red silk. The weight of a single cell is 9-1.2 grams or

1/3 of an ounce.

This view shows the tail tipped upward, which is accomplished

automatically by a pendulum in the bow when the kite makes a dive.

Langley's Steam Aerodrome -- the First Power Driven Airplane to

Fly

The first successful flight of this machine was at Quantico,

Virginia on May 6, 1896. The rudder at the left of this picture

forms part of Lilienthal's gliding machine. In the right-hand corner

of the room is seen the Herring-Arnot two-surface aeroplane which

has been used successfully by Mr. Herring and the Wright brothers.

Herring Dome Kite of 1898

With this kite the center of pressure is almost constant with widely

varying angles of inclination. It's lifting power is also high.

Samples of Brown's Bi-Planes

This type of aeroplane consisting of two following surfaces was

invented about 1878. Langely's aerodrome was built on this plan. But

20 pounds per horsepower can be lifted with this type of machine,

where from 100 to 150 pounds per horsepower can be lifted with the

superposed plane type.

The Motor and Basket of Santos Dumon't's No. 9 Airship.

A blower is arranged to blow on the motor cylinders to cool them

properly. A large bicycle wheel acts as a flywheel and the shaft

carrying the propeller runs forward to the front of the framework.

The model two-surface aeroplane in the left-hand corner is a

motor-driven model which is said to have made numerous successful

flights.

One of the Original Lilienthal Gliding Machines with Which He

Made Hundreds of Successful Flights

This machine has a rudder which is shown in the view of Langley's

aerodrome. Lilienthal succeeded in steering in a sharp curve to

right or left with this machine.

|